Publication Investor briefing: Sexual harassment as material risk

“(...) sexual harassment is a key issue because of its potential to destroy company value” - Louise Davidson, Australian Council of Superannuation Investors[1]

Executive Summary

Sexual harassment in the workplace damages company reputation and social license. It affects operation and labour costs and presents a significant financial risk. And yet companies are not required to provide investors with the information to assess the management of this risk.

In 2020 and 2021 AMP Capital, QBE, Fortescue Metals Group, BHP and Rio Tinto have experienced reputational and other damage over failures to prevent and respond to sexual harassment within their workplaces. Growing attention on this issue has exposed companies that do not have adequate systems in place to protect employees from sexual harassment or to handle complaints. New research has found that sexual harassment reveals significant future problems for companies in terms of profitability, labour costs, and stock performance.

It is increasingly apparent that investors need to better understand the different types of risks posed by sexual harassment, including long term financial risks, operational disruptions and reputational damage. Timely reporting by ASX companies on sexual harassment prevention and response measures is necessary to ensure investors have relevant information to assess company performance and governance of these issues. Companies need to disclose to shareholders how they are implementing the Respect@Work seven domains of change to demonstrate a systematic and thorough approach to sexual harassment prevention and response.

About this briefing paper

This briefing paper examines the financial, governance and operational risks of sexual harassment as well as actions companies can take to manage these risks. It draws primarily on the work of Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins, including her landmark findings from Respect@Work arising from the Sexual Harassment National Inquiry and the follow up report, Equality Across the Board, commissioned in 2021 by the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors.

Despite being a key recommendation of Commissioner Kate Jenkins and being supported by business and industry associations, the Government did not enact Recommendation 17 of Respect@Work which calls for the introduction of a positive duty on all employers to take reasonable and proportionate measures to eliminate sex discrimination, sexual harassment and victimisation. With this key regulation lacking, it is up to companies to ensure their prevention and response measures are sufficient to manage the material risks to employees, workplaces, companies and shareholders, posed by sexual harassment.

Building on the key Australian Human Rights Commission reports, this brief examines the specific shareholder risks and what companies can be doing to mitigate them. Equality Across the Board provided aggregated information on ASX200 companies and sexual harassment. ACCR will take this further by exploring specific sectors, as well as publishing information about how individual companies within these sectors are performing on sexual harassment prevention and response.

A Material Risk

Australia now ranks well behind other countries in preventing and responding to sexual harassment.[2] In 2018 alone, sexual harassment cost the Australian economy an estimated $3.8 billion in lost productivity, staff turnover, absenteeism and other impacts.[3] In its most recent comprehensive survey, the Australian Human Rights Commission found that sexual harassment in Australian workplaces is widespread and pervasive with one in three people having experienced sexual harassment at work in the past five years.[4] In submissions to the National Inquiry into Sexual Harrassment, the Commission heard about a range of financial and other organisational impacts for employers following complaints of workplace sexual harassment. These impacts included time and organisational resources absorbed by responding to and investigating complaints, increase in workers’ compensation premiums, reputational damage and consequent impacts on attracting talent, customers and clients, as well as value to shareholders.[5]

Australian companies and investors would do well to take notice of trends in the United States where there are a considerable number of sexual harassment shareholder resolutions. In 2019 Walmart, Alphabet and Amazon all faced resolutions on sexual harassment.[6] Investment management company, Arjuna Capital, together with a national women’s rights organisation, put a resolution to Comcast/NBCUniversal in June 2021 calling for an independent investigation into its failures to prevent workplace sexual harassment.[7] Importantly, proxy advisor Glass Lewis recommended in favour of the Comcast resolution, saying that “bringing in an independent party to conduct the requested investigation would allow for a more thorough accounting of the issues raised by the proposal”.[8] Glass Lewis further noted that the investigation was of particular importance, as it could signal the seriousness with which the company takes the issue to the company's employees, and could ultimately help the company to foster a more open, diverse, and engaged workforce. Arjuna also put up a resolution to Microsoft for its December 2021 AGM to “independently investigate and confront … transparently claims of sexual harassment and gender discrimination” following allegations of sexual misconduct by former CEO Bill Gates.[9] The resolution urges Microsoft to release an annual transparency report, detailing its sexual harassment policies and investigations into alleged incidents across the company.

Some resolutions have received very strong support. Through the 2021 proxy season, a resolution to Goldman Sachs on mandatory arbitration - which can hide sexual harassment problems - received 53.2%, while a resolution on sexual harassment to solar panel manufacturer, Sunrun, received 59.4%.[10]

Proxy advisors are increasingly considering sexual harassment a material risk. When considering a proposal requesting that XPO Logistics, Inc report on whether (and how) it planned to integrate ESG metrics into the performance measures of executive officers, Glass Lewis noted that: “XPO had faced significant controversy concerning its treatment of employees, having been accused of permitting sexual harassment and gender discrimination. We viewed this as a material issue and one that could pose further financial risks to the company.”[11] Glass Lewis further noted that proposals on diversity, sexual harassment and workforce policies received 28% support (up from 26% in 2019), which “further indicates strong shareholder support and a significant continued investor interest in this issue”.[12]

Proxy advisor ISS notes in its 2021 ESG Themes and Trends that, “even prior to the pandemic, the #MeToo movement exposed companies which did not have adequate protections in place to protect employees from sexual harassment and that complaints were often not handled properly. Stakeholders are holding companies to account on their ‘social license to operate’, demanding greater alignment between management and boards and broader society.”[13]

The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) Governance Snapshot: The Board’s Role in Responding to Workplace Sexual Harassment – a ‘Complainant-Centric’ Approach, published August 2021, found that sexual harassment causes harm to organisations in which it occurs, from a culture, governance and safety perspective.[14] It highlights several areas of risk for boards including a significant legal liability for organisations that fail to prevent and appropriately respond to sexual harassment in the workplace.

Momentum on addressing sexual harassment is growing in Australia and companies cannot afford to wait for government regulation to catch up. Investors in Australia need to understand the different types of risks posed by sexual harassment, including long term financial risks, operational disruptions and reputational damage.

Financial Risk

Investors should take sexual harassment seriously as a long term financial risk.

New research outlined in the Journal of Corporate Finance found that stock performance, profitability and labour costs are all impacted by sexual harassment. The study found that the average effect of a sexual harassment scandal is significant with around 1.5% abnormal decrease in market value over the event day and the following trading day. It also found that the effect is considerably amplified by the involvement of a CEO in the scandal, high news coverage and number of accusers, while companies' self-disclosure of misconduct mitigates the effect.[15]

Another study by University of Manitoba, York University and Université Laval found that sexual harassment reveals significant future problems for companies in terms of profitability, labour costs, and stock performance. The study created a sexual harassment score by calculating the proportion of sexual harassment reports by company and year between 2011 - 2017 to obtain a company-level annual measure of sexual harassment. It found that high sexual harassment scores (the higher the score the poorer the rating) are associated with sharp declines in operating profitability and increases in labour costs.[16] Companies in the top 1% to 5% of the sexual harassment score earned lower risk-adjusted stock returns, representing an annual shareholder value loss of $0.8 to $1.4 billion per harassment-prone company.

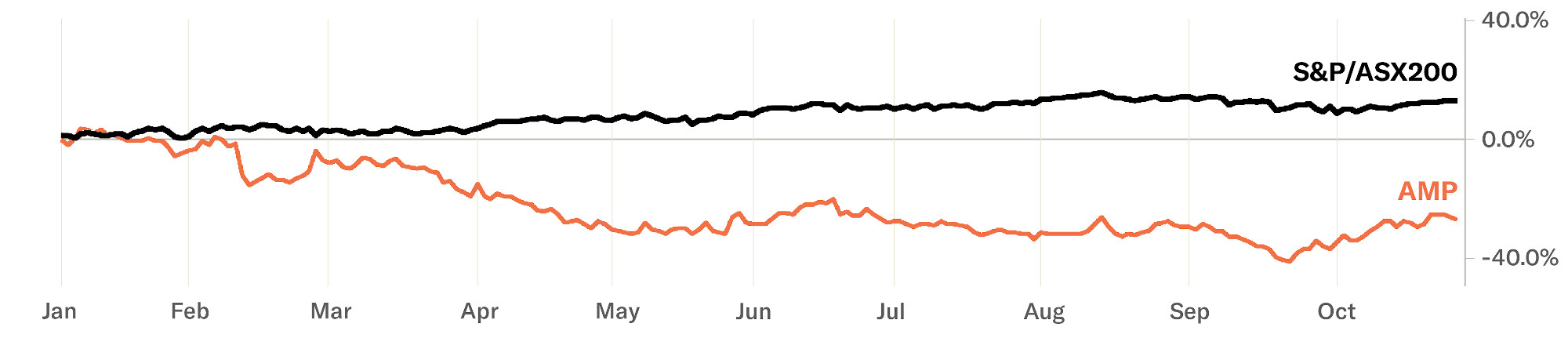

This type of disruption and loss appears to have played out in Australia through 2020 and 2021. In July 2020 AMP promoted its global head of infrastructure equity, Boe Pahari, to chief executive of AMP Capital despite knowing he had been penalised $2.2 million after settling a sexual harassment claim brought by a female subordinate.[17] After AMP appointed Boe Pahari, CEO of institutional investor HESTA, Debbie Blakely, shared concerns about AMP’s handling of the promotion commenting, “[f]ailure to align with society’s values can lead to a loss of financial value for a company and this issue is taken very seriously by long-term investors”.[18] On 16 July 2020, investment consultant JANA publicly cautioned superannuation funds against placing new money with AMP Capital.[19] This was followed by Q Super ending its relationship with AMP Capital, which managed QSuper's $400 million allocation to sustainable investments.[20] AMP’s share price dropped following investor pressure and media reports in 2020 and the company’s woes continued into 2021. While the All Ordinaries Index (ASX: XAO) has gained 10.38% over the 9 months to October 2021, AMP share price is down 27.88% over the same period.[21]

There are multiple factors involved in AMP’s reduced share price, but there is little doubt that the lengthy sexual harassment scandal in 2020 including the resignation of Chairman David Murray and board director John Fraser due to the handling of the issue left a significant mark on the company and contributed to its underperformance.

QBE shares dropped by 7.5% in 12 days from the time a complaint was lodged against chief executive Pat Regan to his dismissal on 1 September 2020.[22] In the U.S, the market capitalisation of Wynn Resorts reportedly dropped an estimated 3.5 billion USD following harassment allegations against CEO Steve Wynn covered in the Wall Street Journal.[23] While these examples represent short term share price impacts, they align with the literature on market signals that generally follow the public airing of evidence of sexual harassment and misconduct.

Reputation and Operational Risks

“A single sexual harassment claim can dramatically reduce public perceptions of an entire organization’s gender equity” - Harvard Business Review[24]

Investors should consider the significant reputational and workforce risks that sexual harassment presents.

The Australian mining industry is one example where sexual harassment is presenting very clear risks. The mining industy has been in the spotlight in 2021 with serious allegations including sexual assault and rape at mine sites.[25]

Recent evidence to an inquiry into sexual harassment against women in the the Fly In Fly Out industry has shown that Australian mining companies are not doing enough to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace.[26] 74% of women experience sexual harassment in the mining industry, but only 17% of women in Australia report harassment in workplaces.[27] The extremely high incidence of sexual harassment in the mining industry are reinforced by results of a 2021 survey of 425 workers undertaken for the inquiry by the Western Mine Workers’ Alliance.[28] The results show that despite years of unions raising concerns around sexual harassment in the industry, one in five respondents said they experienced physical sexual assault, one in five women said they had been explicitly and implicitly offered career advancement or benefits in return for sexual favours, and one in three had received requests for sexual favours and repeated invitations to engage in sexual relationships.

The pervasiveness of harassment is damaging to workforce stability and public perceptions of companies. In the mining industry, for example, many companies have explicit targets on female participation and gender equality. Rio Tinto only managed to increase its percentage of female workers by 0.6% to 19% in 2020.[29] BHP has recently downgraded its ambition for the female percentage of its workforce from 50% to 40% by 2025. Fortescue Metals Group Ltd failed to meet its own target to have a 25% female workforce by 2020 (it achieved 19%).[30] Companies may find that the reputation of the industry as unsafe for women will seriously compromise ambitions towards greater female workforce participation. With growing frustration with the lack of progress in the industry, more women are starting to come forward to talk publicly about their experiences including Astacia Stevens, who shared with the inquiry that she was sexually harassed at both Rio Tinto and Fortescue worksites.[31] Sexual harassment may impact a company that is seeking to increase diversity and inclusion. People of CALD (culturally and linguistically diverse) backgrounds - particularly migrant workers, refugees or others on temporary visas - are disproportionately represented among victims of exploitative workplace practices.[32] The 2018 University of Sydney Women and the Future of Work report found that women born in Asia and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse women reported experiencing sexual harassment at twice the rate of the surveyed population.[33] LGBTQI and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers are also more likely to experience workplace sexual harassment.[34] Ensuring that prevention and response is appropriate for all groups within a workplace will be key to addressing risk and meeting diversity and inclusion targets.

As well as posing a reputational risk to companies, sexual harassment has the potential to cause operational and workforce disruptions. West Australian Mines and Petroleum Minister Bill Johnston said in August 2021 that a failure to report incidents to the government could weaken the industry’s case to bring overseas workers in Western Australia to ease labour and skills shortages.[^35]

The need for improved prevention and response measures is not exclusive to the mining and finance sectors. Sexual harassment is pervasive and widespread across the public and private sectors. The alleged rape of staffer Brittany Higgins prompted a review of parliamentary practice; a senior firefighter has launched legal action against Fire Rescue Victoria; and a government review into sexual harassment in Victorian courts found that 61 per cent of female lawyers had personally experienced sexual harassment while working in the state.[35] Universities have also been in the spotlight with widespread reports of sexual harassment of both students and staff.[36]

However, unlike the public sector and non-listed companies, investors have a financial stake in publicly listed companies. Timely reporting by ASX companies of information on sexual harassment prevention and response is necessary to ensure investors have relevant information to assess company performance and governance of these issues. Listed companies can become examples of good practice that can be replicated by non-listed companies and institutions. Investors have the ability to ask key questions to investees and can become an important force for supporting improvements in the companies they hold.

Governance Risk

Boards must be attentive to sexual harassment prevention and response in order to meet their legal duties to act with reasonable care and diligence, which includes considering foreseeable risks. Recent research by ACSI found that very few boards are currently assuming responsibility and accountability. Equality Across the Board found that less than one-fifth of ASX 200 boards (19%) acknowledge that the board has primary responsibility and accountability for the prevention of and response to sexual harassment.[37] This needs to change if boards want to ensure that the company is taking adequate action to prevent the risk of sexual harassment. In addition to boards’ legal duties, boards also face legal risks.

Employers and their boards can be held vicariously liable for sexual harassment under anti-discrimination laws and in breach of their obligations under workplace health and safety laws.[38]

The risk of breaching safety laws came into focus during the West Australian Inquiry into Sexual Harassment Against Women in the FIFO Mining Industry when the Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety (DMIRS) highlighted reporting failures and possible breaches of the Mines Safety and Inspection (MSI) Act in its submission.[39]

In order to effectively manage these risks, boards should treat sexual harassment with the same priority level as as workplace health and safety, with high expectations of senior leaders to assess and mitigate the risk. The Australian Institute of Company Directors report, which draws on Champions of Change Coalition guidance, finds that boards need to be actively engaged in and informed about the company's sexual harassment response across a number of areas including risk assessment, policies and procedures, consequence management and accountability, recruitment and reward, investigation, support, and external transparency.[40]

Transparency is Key

"Transparency is an effective, relatively low-cost mechanism for engineering positive change." - Respect@Work report 2020[41]

"In the case of workplace sexual harassment, sunlight is the best disinfectant" - Natasha Lamb, managing partner, Arjuna Capital

Companies should publish detailed information on prevention and response measures.

Equality Across the Board found that less than one third of ASX200 companies that responded to their survey reported information relevant to sexual harassment. 14% of respondents did not report at all.[42] The report underlined the importance of transparency as a solution rather than a problem for addressing sexual harassment, noting that “information must be analysed, shared and acted upon for it to be useful. If information is not appropriately escalated within an organisation, risk cannot be effectively and proactively managed by those responsible.”[43]

Respect@Work also emphasised greater transparency as an important measure: “greater awareness regarding incidents, reporting and the ways in which workplaces respond to sexual harassment ultimately serve to inform workplace leaders and assist board members in discharging their duties relating to managing non-financial risk (...).[44] The call for more disclosure is repeated by the Australian Institute for Company Directors in The Board’s Role in Responding to Workplace Sexual Harassment. The report found that “longer-term, proactively supporting greater transparency can address systemic drivers of sexual harassment and improve culture within an organisation.”[45]

Reporting on the overall number of incidents per year is one step that BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals Group have taken, but there is much more information that needs to be shared for investors to be able to assess whether companies are addressing prevention and response comprehensively.

Companies can start publicly sharing key policies, procedures and risk assessments to demonstrate a culture of accountability and show in detail the range of actions the company is undertaking to prevent and address sexual harassment.

What Companies Should Be Reporting

This section outlines key indicators that companies should publicly report against for investors. In order to demonstrate a systematic and thorough approach to prevention and response, companies need to disclose how they are implementing the Respect@Work seven domains of change. Each domain outlines actions that companies could take in each of these areas. The indicators below are part of a set of questions that ACCR will be asking top ASX100 companies in the extractives and financial services industries. Findings will be published in the first half of 2022.

- Leadership—the development and display of strong leadership, that contributes to cultures that prevent workplace sexual harassment.

- Is preventing and managing incidents and risks of sexual harassment part of Directors’ responsibilities?

- Is sexual harassment treated the same as workplace health and safety at the board level with the same expectations on senior leaders to assess and mitigate risk?

- Risk assessment and transparency—greater focus on identifying and assessing risk, learning from past experience and transparency about sexual harassment, both within and outside of workplaces, to mitigate the risk it can pose to businesses. This can help improve understanding of these issues and encourage continuous improvement in workplaces.

- Has the company undertaken an assessment (within the last two years) to identify drivers and hazards that may lead to sexual harassment in the company?

- Does the company share de-identified or aggregated data about sexual harassment that occurs in the workplace at periodic intervals, including providing information on what steps were taken to resolve complaints and how long this process took?

- Culture—the building of cultures of trust and respect, that minimise the risk of sexual harassment occurring and, if it does occur, ensure it is dealt with in a way that minimises harm to workers. This includes the role of policies and human resources practices in setting organisational culture.

- Do the company sexual harassment policies and processes sit alongside or within a broader gender equality strategy that addresses the four gendered drivers of sexual harassment?

- Has the company considered the experiences of different groups of workers in measures to create a workplace culture where sexual harassment will not be tolerated?

- Knowledge—new and better approaches to workplace education and training, to demonstrate an employer’s commitment to addressing sexual harassment and initiate change by developing a collective understanding of expected workplace behaviours and processes.

- Are workers and managers at all levels provided mandatory training on how to prevent sexual harassment, how to respond if they experience or witness sexual harassment and how to report it?

- Are board Directors and CEOs provided mandatory training on how to prevent sexual harassment and their responsibilities?

- Support—prioritising worker wellbeing and provision of support to workers before they make a report, after they report and during any formal processes.

- Has the company publicly committed to the ability for workers to speak openly about experiences in a manner and at a time of their choosing?

- Has the company made a public commitment to avoid the use of non-disclosure contracts in agreements unless a non-disclosure contract is requested by the victim?

- Reporting—increasing the options available to workers to report workplace sexual harassment and address barriers to reporting. Creating new ways for employers to intervene to address sexual harassment, other than launching a formal investigation. Adopting a victim-centred approach to the way investigations are conducted when a report is made to minimise unnecessary harm to workers.

- Does the company provide victims of sexual harassment with multiple avenues to get information and support, and raise concerns including less formal options?

- Does the company have a victim-centred approach to they way that it addresses sexual harassment complaints?

- Measuring—the collection of data at a workplace-level and industry-level to help improve understanding of the scope and nature of the problem posed by sexual harassment.

- Has the company publicly disclosed the process (including timelines) and expectations for investigations as well as the actions that may result if an individual is found to have engaged in sexual harassment?[46]

Contact

Daisy Gardener | Director of Human Rights | daisy.gardener@accr.org.au

Please read the terms and conditions attached to the use of this site.

ABC News, “How will first Respect@Work recommendations affect women in workplaces?” 14 September 2021, link ↩︎

The Australian Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report 2020, p.9 ↩︎

Deloitte Access Economics, The economic costs of sexual harassment in the workplace, 2018, link ↩︎

Australian Human Rights Commission, Everyone’s Business: Fourth National Survey on Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, 2018, p.8 ↩︎

The Australian Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work: National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces 2020, p.285 ↩︎

Ceres, “Adopt board oversight of workplace sexual harassment (WMT, 2019 Resolution)”, 2019, link ↩︎

Aruna Capital, “Pressure builds on Comcast/NBCUniversal after it fails to kill June 3rd Shareholder vote on workplace sexual harassment”, 3rd June 2021 ↩︎

Glass Lewis, 2020 Proxy Season Review, p.31 ↩︎

BusinessWire, “Arjuna Capital Shareholder Resolution: Microsoft Needs Independent and Transparent Investigation of Gender Discrimination, Sexual Harassment”, 16 June 2021 ↩︎

As You Sow, “Record Breaking Year for Environmental, Social, and Sustainable Governance Shareholder Resolutions”, June 2021, link ↩︎

Glass Lewis, 2020 Proxy Season Review: Shareholder Proposals, 2020, link ↩︎

Glass Lewis, 2020 Proxy Season Review: Shareholder Proposals, p.29 ↩︎

ISS, Volatile Transitions Navigating ESG in 2021, ESG Themes and Trends, 2021, p.41 ↩︎

Australian Institute of Company Directors, AICD Governance Snapshot: The Board’s Role in Responding to Workplace Sexual Harassment – a ‘Complainant-Centric’ Approach, August 2021 ↩︎

Borelli-Kjaer, Mads & Schack, Laurids & Nielsson, Ulf. (2021). #MeToo: Sexual harassment and company value. Journal of Corporate Finance. 67. 101875. 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101875. The study identifies the impact of reported sexual harassment on firm value through the use of 200 unique incidents ↩︎

Au, Shiu-Yik and Dong, Ming and Tremblay, Andreanne, Employee Sexual Harassment Reviews and Firm Value (July 30, 2021). ↩︎

Michael Rodden, “AMP's Boe Pahari paid a $2.2 million penalty ↩︎

Aleks Vickovich and Joanna Mather, “Big Super leans in on AMP's gender problem”, The Australian Financial Review 15 July 2020 ↩︎

Aleks Vickovich, “Pahari fallout threatens AMP's super fund rivers of gold” The Australian Financial Review, 16 July 2020 link ↩︎

Aleks Vickovich and Michael Roddan, “QSuper yanks $400m ethical mandate from AMP”, The Australian Financial Review , 18 July 2020 link ↩︎

ASX, “AMP Share Price and Company Information”, accessed 12 October 2021, link ↩︎

ASX, “QBE Share Price and Company information”, link ↩︎

Fortune, Wynn Resorts Loses $3.5 Billion After Sexual Harassment Allegations Surface About Steve Wynn, 30 January 2018, link ↩︎

Harvard Business Review, How Sexual Harassment Affects a Company’s Public Image, 2018 ↩︎

Eliza Borrello, “Sexual assault allegations at WA mine sites in Senate spotlight” ABC, 19 July 2021, link ↩︎

Western Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into Sexual Harassment against women in the FIFO Mining Industry, 2021 ↩︎

The Australian Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report, 2020, p.221 and Everyone’s business: Fourth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces, 2018, p. 5 ↩︎

Western Mine Workers’ Alliance submission to Western Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into Sexual Harassment against women in the FIFO Mining Industry, August 2021, link ↩︎

Rio Tinto, “2020 Performance” link ↩︎

Joe Aston, “BHP moves goalposts on gender target” Australian Financial Review, 15 September 2021, link , Fortescue Metals Group, Sustainability Report FY 20, p.29, link ↩︎

Eliza Borrello, Eliza Laschon, “Sexual harassment inquiry told female mine worker allegedly propositioned for sex at Rio Tinto, FMG” 17 September 2021, link ↩︎

Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work: National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, p.208 ↩︎

Marian Baird, Rae Cooper, Elizabeth Hill, Elspeth Probyn and Ariadne Vromen, Women and the Future of Work, 2018, link ↩︎

Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work: National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, p.192 - 200

[35]: Brad Thompson, “Mining giants face outrage over sex crimes silence”, Australian Financial Review, 20 August 2021, link ↩︎Josh Bornstein, “Why change at the top will make women feel safer”, The Age, 15 September 2021, link, Review of Sexual Harassment in Victorian Courts, 2021, link ↩︎

The West Australian “WA universities report dozens of sexual assault and harassment complaints on students and staff” 6 September 2021; The Australian Human Rights Commission conducted a national, independent survey of university students to gain greater insight into the nature, prevalence and reporting of sexual assault and sexual harassment at Australian universities.It found that around half of all university students (51%) were sexually harassed on at least one occasion in 2016. ↩︎

Australian Human Rights Commission, Equality Across the Board, 2021 ↩︎

Australian Institute of Company Directors, AICD Governance Snapshot: The Board’s Role in Responding to Workplace Sexual Harassment – a ‘Complainant-Centric’ Approach, August 2021, p.6 ↩︎

Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety submission to Western Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into Sexual Harassment against women in the FIFO Mining Industry, August 2021 ↩︎

Australian Institute of Company Directors, AICD Governance Snapshot: The Board’s Role in Responding to Workplace Sexual Harassment – a ‘Complainant-Centric’ Approach, August 2021 ↩︎

Australian Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work, 2020, p.628 ↩︎

Australian Human Rights Commission, Equality Across the Board, 2021, p.14 ↩︎

Australian Human Rights Commission, Equality Across the Board, 2021 ↩︎

Australian Human Rights Commission, Respect@Work, 2020, p.629 ↩︎

Australian Institute of Company Directors, AICD Governance Snapshot: The Board’s Role in Responding to Workplace Sexual Harassment – a ‘Complainant-Centric’ Approach, August 2021 ↩︎

Minerals Council of Australia, Industry code on Eliminating Sexual harassment, March 2021 ↩︎